Swept Away (The Zine)

Readers:

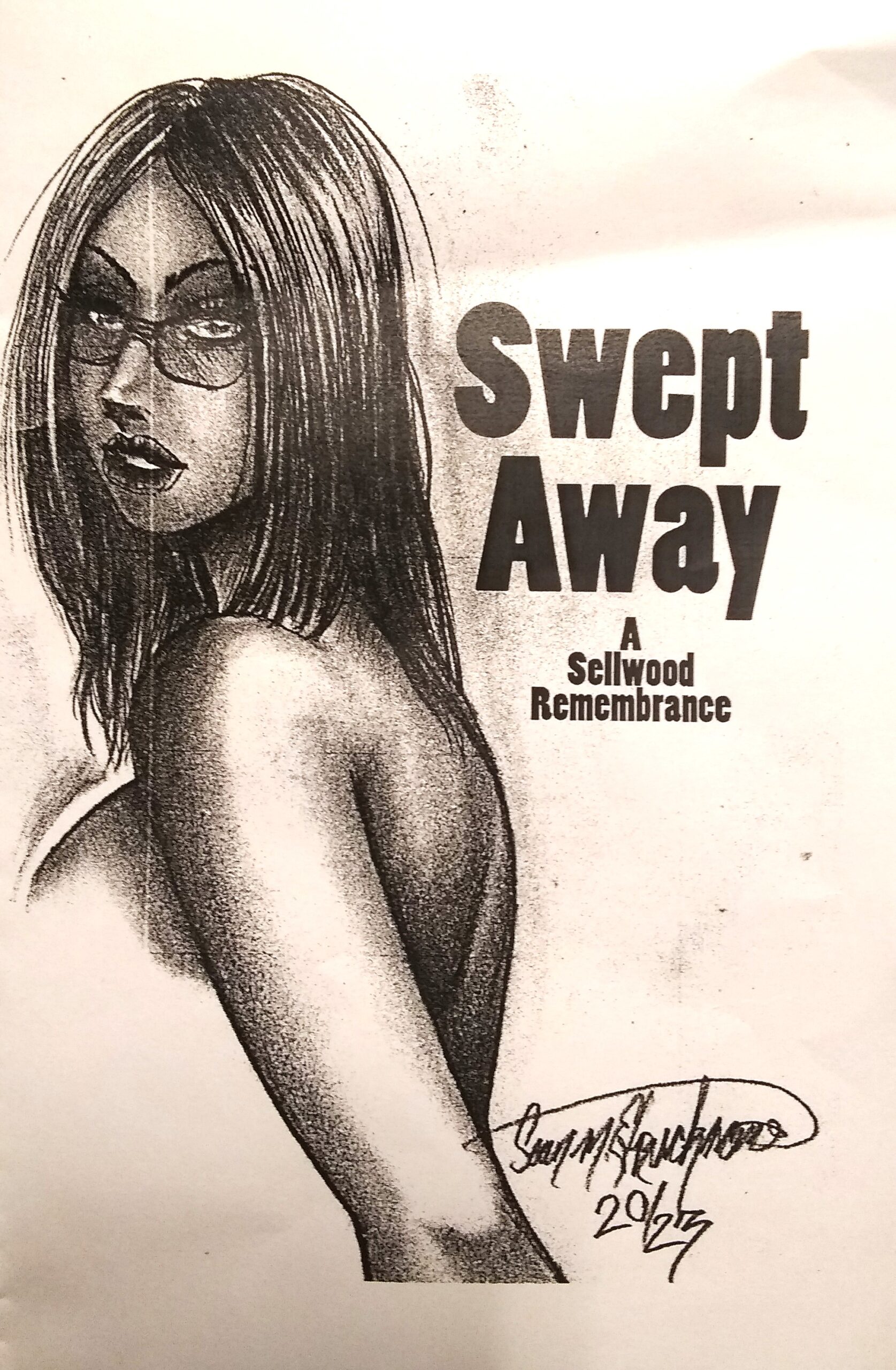

Two weeks ago I posted a story called Swept Away that reported on what I had learned about the man who was drown in Johnson Creek in early December. What you are about to read is the zine I produced to honor this man’s death and distributed in street libraries around the neighborhood where he died. I printed 100 copies and rewrote the text in the third person, which often makes a piece of writing exude more power. The cover art was drawn by the deceased man, Sean Struckman.

Swept Away

At approximately 7:30 AM on December 4, 2023, high water on Johnson Creek in SE Portland swept away a man under the Tacoma Street bridge, the site of a homeless encampment.

Television crews broadcast from the bridge site and interviewed a resident of the encampment. He said the deceased man was his best friend, a tattoo artist, and they’d tried to save him but the current was too wild. It was unclear from the reports whether the missing man resided in the encampment, but he was there nonetheless.

The man’s body was discovered by a downstream homeowner two days later. He has yet to be identified to the public, perhaps he never would be.

John Donne wrote, “Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind.”

How are we diminished by the loss of an anonymous man swept away in a homeless encampment?

Maybe he’s not anonymous.

Five days after the death, if one looked down from the bridge to the encampment, it appeared as if a mortar round had scored a direct hit. People still lived there. Had they erected a memorial to the man? None was visible from the bridge.

A side street off the bridge offered closer inspection. There was a well-worn path that led straight into the encampment. At the entrance to the path were several neat piles of split firewood. This was grade A Doug fir, seasoned and obviously not harvested from the woods in the area. Someone in the neighborhood was supplying the encampment with firewood to help them survive.

Fifty feet from the encampment a newly razed former manufacturing plant on a roughly two-acre lot was being graded and prepped for future construction. A thought materialized: this was a perfect spot for a temporary homeless encampment. It had water and power already on site. It had sewer hookups. It was surrounded by concrete and railroad tracks. There wasn’t a residential dwelling in site. There were already 20 or 30 homeless people living along the creek and in nearby RVs within shouting distance. The neighbor across the street was a public golf course.

If there were any urgency addressing the emergency of homelessness in Portland, this site could host temporary housing for 30-50 people in purchased second-hand trailers and fifth wheels. It would take two weeks to set up. Hire an onsite manager. Establish a residents’ council and draw up some rules. No accumulating shit. One strike and you’re out.

Two men were coordinating the grading and surveying of the site. They were asked what was planned for the space.

“Storage units. We’ll break ground in a month and have them opened by late spring.”

Storage units. Heated no doubt. Oregon probably builds more heated storage units than it erects unheated temporary housing units.

Swept away. Such poetry in that vivid image; it has the force of a folk song commenting on monumental loss. (Think “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” or that song Dylan wrote about a bear mauling people at a picnic.) Someone should write a song for this drowned man. Someone should write an elegy for this drowned man. Someone should write something for him.

Here you are:

A day later, at a dive bar not far from Johnson Creek, the drowned man’s story emerged. It emerged courtesy of a bartender in the joint, who had spent two days consoling the distraught man who had appeared on television and spoke of the loss of his friend. The man alive was Kenny. The dead man was Sean.

Sean Struckman was around 40 years old. He had a young son who lived in the Portland area with his mother, Sean’s ex. Sean was not homeless when he died, but perhaps had been at some points in his life. He lived in an apartment in North Portland but often traveled to Sellwood for days at a time to hang out in the encampment with friends. Sean was a small man and exuded a skater sort of vibe. He admittedly suffered various mental illnesses.

Sean was a tattoo artist and tattooed housed locals and homeless people in the neighborhood in their residences. He was not affiliated with a shop. The bartender had bought some of his tattooing equipment for her daughter when she became interested in tattooing as a possible career. After Sean’s death, the bartender gave Kenny one of Sean’s tattoo guns as a memento of his friend.

Kenny told the bartender that Sean had thrown a seat cushion into the current before he ended up there. Kenny wasn’t sure why. He thought Sean might have jumped into the creek as a kind of joke or was just horsing around with nature, but he didn’t believe his friend committed suicide. Who really knew? No one would ever know for sure.

What Kenny did know for sure was the last time he saw Sean. The current was ripping and roiling and turned Sean momentarily around. Kenny got one final look at Sean’s face before he went under and it registered a look that he would never forget: I fucked up!

Kenny hadn’t slept since he’d last seen Sean’s face.

The next day in the bar more of the story unfolded, as did samples of Sean’s artwork.

A man was in the joint. He rolled up his left sleeve and displayed NATIVE inked on his forearm. He said, “I think I was the last person he tattooed.”

Sitting at the bar, the man recounted the night before Sean died. He had been with him near a convenience store. Sean was extremely upset about a breakup with a woman. He had two black eyes. In the morning, he ended up in Johnson Creek at flood stage and lost his life.

The bartender produced some of Sean’s artwork. They were two pencil drawings of women and were quite arresting. Had either of this flash made it onto someone’s body?

Sean’s art lives on other bodies. It adorns the cover and back cover of this publication.

The creek may have swept him away, but not his art, and thus not his spirit.