RIP Bud Clark

The great Bud Clark passed away February 1. The former Portland Mayor, a certifiable Oregon legend, died from congestive heart failure at the age of 90.

It was my sincere pleasure to have met Bud Clark on multiple occasions over the past decade. It all began when he came up to me in a brewery in Astoria and introduced himself. We had an impromptu beer together and talked about his extraordinary career as mayor and my connection to it. I was living in Portland during most of his tenure and recalled all the major events, including the staging of the inaugural Mayor’s Ball, a one day rock festival held at the Memorial Coliseum to retire his campaign debt! To my knowledge, it was the only event of its kind in American history. I was there and it was wild.

Several years after meeting Bud, he participated in a Zen Buddhist-themed writing workshop I held and it was pure joy to have him in attendance and to hear him read some of his writing. I encouraged him to write his memoir and that I would assist in any way possible. I told him it would be an important book for Oregon history and to have his thoughts and insights on many of Portland’s seemingly hopeless problems.

Later, I met him and a friend at the Goose Hollow Inn, the semi-famous tavern he once owned and operated (his daughter took it over). Again, I urged him to write his memoir. He seemed enthusiastic about the idea and told me his family was in possession of his memorabilia including a lot of film footage.

The last time we corresponded was by email and he thanked me for recommending a book, The Snow Leopard. He thought it was an incredible read.

That was almost four years ago and I have no idea if Bud started the project.

What follows is the story of the inaugural Mayor’s Ball. It was one of the original essays in my 2009 Oregon sesquicentennial anthology, Citadel of the Spirit. It was written by the late, great Billy Hults. You talk about a helluva weird and glorious tale!

RIP Bud. You made my life in Portland better, and so much more interesting. It almost feels like Portland needs another kind of Bud Clark to address the various crises engulfing the city because whatever the current mayor and city council are doing by the progressive book, isn’t cutting it. It’s time for something entirely new, unconventional. Portland and Oregon used to do that sort of thing.

The Mayor’s Ball / Billy Hults

It was Christmas Day 1983 and I sat alone in the Goose Hollow Inn in Southwest Portland. I’d just finished a shift as janitor of the place and had made coffee. I waited for Bud Clark, the Inn’s owner, who was coming down to get some beer for the open house he held for employees, friends and family every Christmas and Thanksgiving.

I’d known Bud for years and recently moved into the Goose Hollow neighborhood, into a small trailer I parked at the end of Southwest Eighteenth, right below the painter Henk Pander’s house in the shell of a former garage. I’d covered the trailer with tarps and draped blackberry vines over it because it was illegal to live in a trailer within the city limits. Bud had given me work as a part-time janitor, so John Moses, the regular janitor could take some days off. John was a Reed College graduate with a Masters in history. I was the first janitor at the Goose who didn’t have at least a BA.

When Bud showed up he was with Peter, one of the bartenders, and they were in a heated discussion about the upcoming mayoral race. Frank Ivancie was the incumbent and so feared by all the professional politicians, that he was running unopposed. Ivancie was be remembered by most of us for sending the Portland Police into the downtown Portland park blocks to beat up demonstrators in the aftermath of the Kent State shootings. He called himself Democrat and was the head of Democrats for Reagan.

Bud was a registered Republican, but he was more of a Tom McCall Republican than a Reagan Republican. Bud loved Portland and had been involved with community service for years. Every Thursday for over ten years he would disappear for a few hours and no one knew where he went, until someone learned he was volunteering to deliver Meals on Wheels to the elderly. He’d attended Reed College, was a former Marine, and had been running one of Portland’s favorite taverns for decades.

I don’t remember exactly what Bud said, but I gathered from the conversation that he’s decided to run himself. Everyone thought he was kidding, until they looked him in the eye. He was serious; his city was too important to him to leave it in the hands of Frank Ivancie.

Bud had no political experience, no organization, and hardly any money of his own. But he was serious. He took out a loan on his house and filed to run for Mayor. People thought it was some kind of stunt, but the regulars at the Goose knew better. They knew from experience that when Bud said he was going to do something, it got done. Overnight, the Goose became a campaign headquarters. We all got out our address books and Rolodexes and created a mailing list of possible supporters. Phil Thompson, a local architect, was put in charge of fundraising events and he came to me looking for help with bands. Most of the musicians in town already hated Ivancie, and a lot of them occasionally hung out at the Goose. Bud’s wife, Sigrid, was also violinist with the Oregon Symphony, so getting bands to perform benefits was easy.

The volunteers turned the Goose into a hotbed of activity. They called themselves the “sweaty four hundred” a reference to the “Charge of the Light Brigade” riding into the valley of death. We staged the first event at the Horse Brass Pub in Southeast Portland and threw together a band. The media showed up and Bud officially declared his candidacy. He wore a rose in his lapel because Portland is the Rose City, and he proclaimed “Bud Clark is Serious,” which became the slogan for the campaign. He also greeted folks with “Whoop Whoop,” his trademark phrase.

The sweaty four hundred were tireless. Every day a new idea would come up and be implemented. People came out of the wood work. One of the regulars at the Goose had a flower shop and the day after Valentine’s Day she brought over all of the unsold roses. We tied little tags on them in the back room at the Goose and took them to the Blazer game and gave them away to people waiting in line. The tags said “A bud from Bud” or something like that. The media took notice of all the unconventional events and we started getting coverage.

People started to come around the Goose to see what this was all about. Many ended up volunteering and we set up an office in the building behind the Goose that housed a phone bank and volunteer staff. We put up billboards saying “Bud Clark, the People’s Choice.” Bud decided to visit every bar and tavern in the city, and talk to folks. I think he actually did it.

I think it was during the St. John’s Parade that really started us thinking we could win. Ivancie and Bud were both in the parade, and when Ivancie’s car drove past people applauded politely or even booed. But when Bud’s car went by, folks yelled “Whoop Whoop!” and waved and cheered.

Ivancie finally began to grasp that the attention Bud was receiving was getting out of hand. He took out an ad saying that Bud had no experience and was an embarrassment to the city. He said that it was all very well to run in the primary when no one was really paying attention, but that in November, in the general election, people would realize that Bud couldn’t compete with his experience and his organization.

Ivancie never had a chance to find out if any of that was true. The primary was scheduled for May and if no candidate received over fifty-percent of the vote, a runoff between the top two finishers would be held in November. To the delight and amazement of almost everyone, Bud beat Ivancie in the primary! The media went crazy and the calls poured in. People from all over flocked to the Goose the morning after the election and Portland would never be the same. It seemed like the whole country knew about the Goose now and wanted to meet the bartender who became Mayor.

One day Phil Thompson took me aside and explained that Bud had gone seventy-five thousand dollars in debt and that we needed a fundraiser to pay it off. We decided to throw an Inaugural Ball and I was going to be in charge of the music. We felt that since Bud wouldn’t officially become Mayor until January 1, we would hold the Ball January 4 at the biggest room in town, the Memorial Coliseum. It could hold fourteen thousand people. Phil said we could charge ten dollars each and maybe draw seven thousand and pay down part of the debt.

Well, Bud agreed to the idea, even when I told him there were thirty-three bands that had helped during the campaign and they would all probably play, plus the Portland Jr. Symphony, and I wanted a professional sound system. If we were going to do it, it had to be done right. Phil Thompson gave me a check for a deposit and I took the bus to the Coliseum, and booked the date.

January is a pretty risky month in Oregon to throw a gig. We’d been experiencing ice storms and all sorts of bad weather in December. The manager of the Coliseum, Carl, a tough old German guy, was used to dealing with professional promoters, and when I told him my idea for the gig he almost laughed in my face. He listed all the things that could go wrong. He said things weren’t done the way I’d envisioned, and that he would not be held responsible for what was surely was going to be a fiasco.

My plan called for two stages on the main floor, each with a full sound system, and the manager said there wasn’t a sound company in town with enough equipment to do two stages. I also planned to have four stages on the concourse that surrounds the main room, each with a small sound system and a sound man. Each of the thirty-three acts would do a thirty-minute set, which figured out to five and a half hours of music on six different stages, leaving five minutes leeway for the bands to set up and tear down between acts. It was a schedule no one could be expected to keep, especially musicians. The bands on the main stages would have a half an hour to set up and tear down because one stage would be dark while the other was playing.

Gary Keiski and John Miller, regulars at the Goose who had helped on the campaign, joined me in the former campaign office behind the Goose, and with three-by-five cards with the various acts names on them, we went about making up a schedule. We found out that Carl was right: no sound company in town had enough equipment to outfit two stages at once in such a large venue.

Dave Cutter at Sundown Sound had volunteered during the campaign and said he would run one stage. For the other stage, I got in touch with Jody, a tall redhead who had been there for me before. She happened to be married to the owner of GreatNorthwest Sound, one of the biggest sound companies on the West Coast. She helped me out and we now had enough equipment for the main stages.

There was always something more to do. We called the stagehands union and negotiated for a better rate and the right to use non-union roadies. The Jr. Symphony agreed to play but we needed chairs and music stands for seventy musicians. I think it was Gary who called Lincoln High School and got them to loan us the chairs and music stands.

Phil was the overall boss of the operation and was to serve as Master of Ceremonies at the Ball. We needed a honcho to coordinate the roadies and security and enlisted Buck Munger, who also arranged for a Marine color guard to parade the colors at the Ball. We talked James DePriest, the conductor of the Oregon Symphony Orchestra, into introducing Bud. The Imperial Brass wrote a special introductory piece to herald Bud’s entrance. My plan was to have something like I had seen at the Oregon Country Fair, where you would walk from one stage to another and each would have a different kind of music. The experts told me that it would end up as a cacophony, but I didn’t think that was as important as the fact that you had so many choices.

The local professional promoters like Double T and John Bauer Concerts told me to forget about all this stuff and just get the name bands and forget about all the little bands that had volunteered during the campaign. After all the object was to raise money, wasn’t it? Well, yes, I agreed, but I said it was also important how you raised the money.

As we got closer to the date, the politics of the event began to surface. Lobbyists who wanted the Mayor’s ear came to the Goose to pitch. I found myself talking to a guy from a fireworks company who wanted Portland to allow fireworks to be loaded and unloaded at the Portland docks. He also happened to volunteer to stage a fireworks display for the Ball so we talked. The Steel Bridge just south of the Coliseum was being repaired and the on-ramp was closed off. We received permission to set up the display there so it could be seen through the glass walls of the Coliseum. It would be our grand finale at midnight.

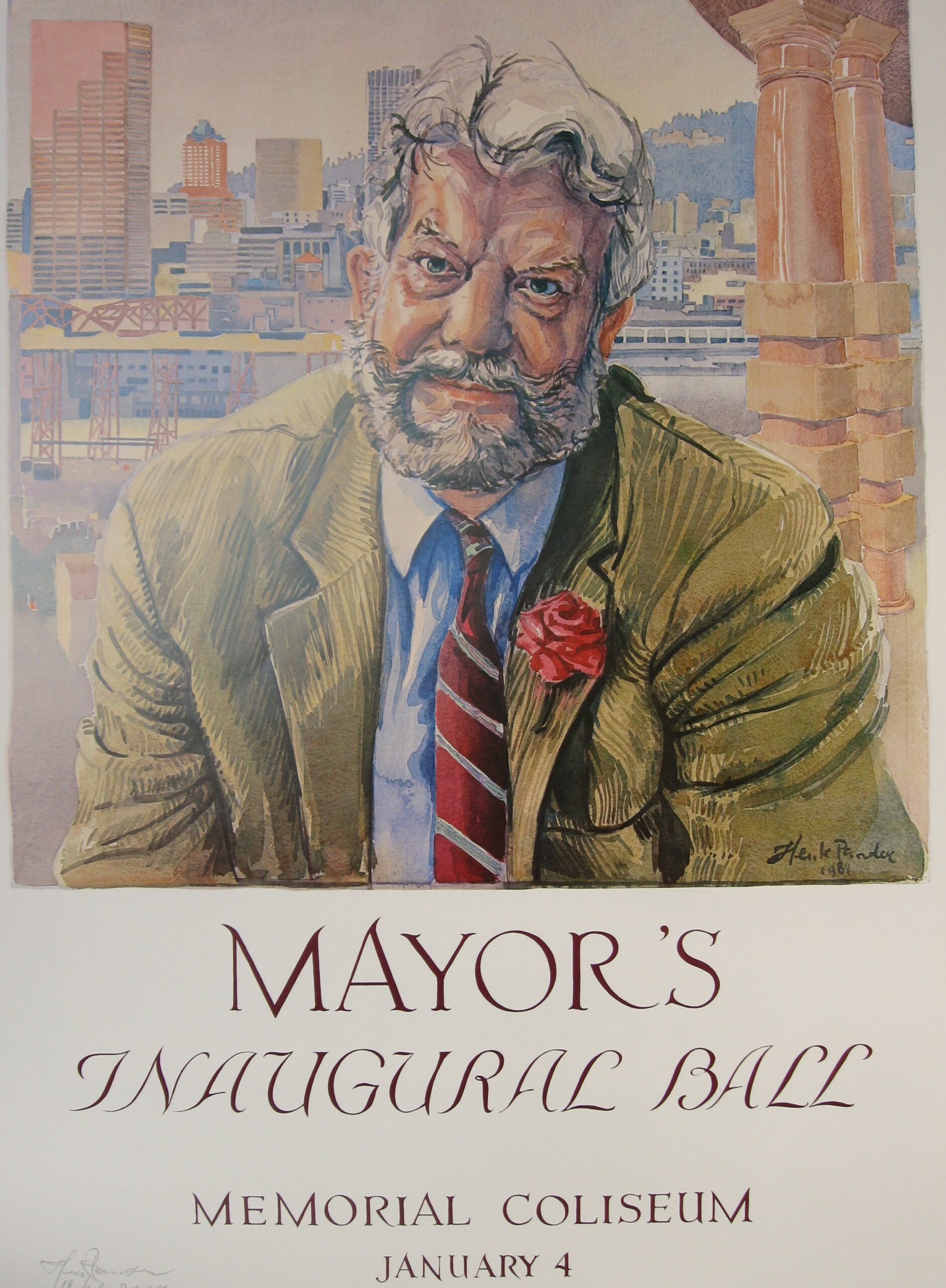

More and more people were saying the event was getting out of hand: the Jr. Symphony, a twelve-piece jazz all-star band, my own twenty-two-piece Billy Foodstamp and the Welfare Ranch Rodeo, The Kingsmen of “Louie Louie” fame, a Marine color guard and now fireworks! They were right. It was getting out of hand but I’d forgotten bagpipes. We found a piper from the Clan MC or something like that. Toward the end, we got Pander to do the poster and enlisted Michael Burgess to write the copy and the introduction in the program. Once it was all laid out on paper, it didn’t look quite so crazy.

Early sales weren’t encouraging. All of this activity was going on during the Christmas holidays and people were often out of town or at least not at their desks when we called for help. But it didn’t matter, we’d reached a point of no return.

Somehow the day arrived clear and dry. We gathered at the Coliseum at 10 A.M. The sound guys had already loaded in and Gary Ewing was setting up his light show. As the day rushed on the chaos slowly became order. The mix of enthusiastic volunteers and seasoned professionals worked well together. When the sun started to go down the lines outside started to grow. We opened the doors at 5 P.M. and it seemed like everyone in Portland streamed in. I must have walked fifty miles that day trying to find and solve problems.

It was the largest gathering of musicians under one roof in the history of Oregon.

The first big moment of the night was Bud’s entrance. I had to fight very hard for my idea. Most people just wanted Bud to appear on stage and say a few words. I wanted him to walk from one end of the room to the other, through the crowd, greeting the people. Security went nuts! They said they would need a flying wedge to get him through and he’d still be mobbed. That’s where the Marine color guard and the bagpiper came in. Maestro James DePriest was on the north stage in the main room and was introduced by Phil Thompson, who stood on the south stage. DePriest said some kind word about Bud, and as the Imperial Brass played its special piece, he directed the now capacity crowd’s attention to his right, where a spotlight was focused on the flags of the United States, Oregon and the Marine Corps.

Then, behind the color guard the piper began. Security was trying to move the crowd, but when the Sergeant of the Guard barked his command, “Forward, march,” and moved out in a slow, measured pace, the crowd just parted on its own. Bud and Sigrid followed the piper and waved and shook hands as the procession move toward the south stage. When they reached the south stage, Bud made a short speech thanking almost everyone in the world.

I was on the north stage with my band, and when Bud was done ‘whooping,’ he introduced us. At 11:30 P.M. the Kingsmen came on the south stage, and after playing some of their hits, finally told the crowd that this was the last song of the evening, and yes, it was going to be “Louie Louie.” We lit up the north stage and as many musicians as possible plugged in or grabbed microphones and the whole place went wild in an orgy of “Louie Louie, oh, we gotta’ go now.”

Phil Thompson finally called a halt to the madness and directed everyone’s attention to the south windows. The fireworks went off, sending up huge flowers of light blazing away in the darkness. People rushed to the south windows, and then outside to watch. At 12:30 A.M. the Coliseum was almost empty and I was standing on the floor of the main room with Carl. He was supervising his crew who were getting ready to freeze the floor for a hockey game the next day. He shook his head and said, “I don’t believe it.” Then he smiled for the first time since I’d met him.

We grossed over seventy-eight thousand dollars but because of expenses, another fundraiser was needed. Overall, the Ball netted forty grand in six hours. People started talking about making the Ball an annual event. It had been so successful that we got national press, and the word was out that Portland had a great music scene. I agreed to coordinate a second ball with the proceeds going to local charities and a group of folks in the music scene got together in my office and formed the Portland Music Association. Eventually there were eight Mayor’s Balls, one of which made the Guinness Book of World Records for the most bands under one roof in one night: eighty-eight bands on eight stages in eight hours. Billboard Magazine did a major article on the Balls and several bands were scouted and signed for national labels at the Ball.

Bud was reelected for a second term and brought Portland national and international attention with his lederhosen, bicycle riding, the rose in his lapel, his “whoop whoop!” and “Expose Yourself to Art” poster. Once he left office after two terms he went back to the Goose. When Vera Katz was elected mayor, she declined to lend the name of her office to the Mayor’s Ball and it ended.