The Alpine Tavern: One the Great Lost Oregon Books of All Time

One of the great lost Oregon books of all time was brought to my attention last summer by my former great collaborator. She found it in an upstate New York estate sale or thrift store. How it ended up there is probably a novel in itself. In all my three decades of combing Oregon libraries and used bookstores, I had never seen it.

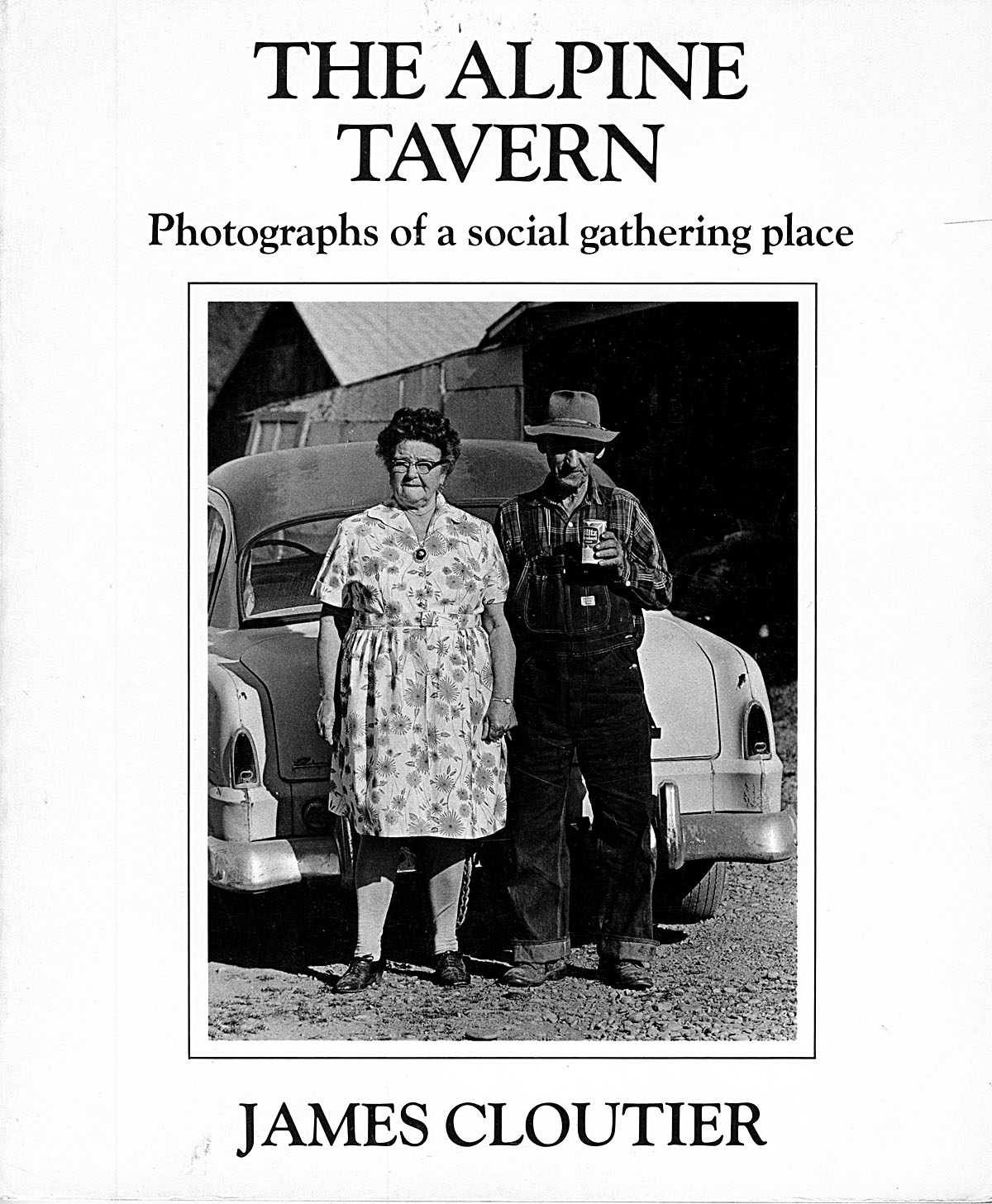

The book is called The Alpine Tavern: Photographs of a Social Gathering Place. All text and photographs were by James Cloutier. Image West Press of Eugene published the 78-page, softcover, black and white, coffee table-sized book in 1977. It is one of my prized possessions and the collaborator surprised me with a gift from clear across the country. When I opened the package, took out the book, and perused this extraordinary work of American ethnography, I could not believe what I was seeing or that she knew me so well to send it. She could read my literary mind better than anyone and I feel totally lost without her magical intuition in my creative and personal life.

It is perhaps the original Oregon Tavern Age literary artifact. It was going to be the model for a print black and white version of my e-book, Oregon Tavern Age (OTA): Sketches from Coastal Drinking Life, that the collaborator was going to illustrate and design. We were going to print it up as a magazine and distribute it for free in every dive bar and tavern on the Oregon Coast in an unprecedented project. We take the OTA stories to the OTA regulars.

The book’s focal point is the Alpine Tavern, built in 1936, located in Monroe, Oregon, rural Benton County, in the foothills of the Coast Range. Logging country or what used to be logging country. I have driven Highway 99E through Monroe dozens of times during the course of my gigging life but never took a side road to find this joint. Sometimes you need to take those side roads in life. Isn’t that where the interesting moments in life occur? That’s certainly where you find the greatest OTA establishments.

Cloutier reveals in the book’s introduction that he first visited the Alpine Tavern in 1968 while shooting photographs of the area’s many old and crumbling buildings. Later he began visiting the tavern in earnest and made the tavern’s regulars the subject of his portraiture. Clearly he fell in love with the place and I know the feeling well when you find places like this. They have inspired some of my most original writing about Oregon because I always seem to walk into incredible stories whenever I step inside these joints.

The photographs are like the Mount Rushmore of OTA images. The men and women are fine, weathered, wearing suspenders and dresses, talking, laughing, playing pool, pinball, a bowling game, shuffleboard and working the jukebox, drinking quarter drafts or 50-cent cans of Pacific Northwest lagers then brewed in the Pacific Northwest by union men. The only brands of beer spotted in the photographs are Blitz and Olympia.

I’ve perused this book dozens of times and always find a new perfect detail in Cloutier’s photographs. I would have loved to hear what these people talked about in 1977. That was a long time ago in Oregon and much has changed.

According to the Internet, the Alpine Tavern is still open. I simply must visit one day. I must find a way to publish Oregon Tavern Age as a print publication, include a new chapter on Cloutier’s remarkable book, and distribute it all throughout OTA country.

But I will need a new collaborator because the former one is lost to me forever.