Elizabeth Bishop and the Homeless of Portland

My Dad and I were on the back deck on a Saturday afternoon. Our time living together was growing short. Less than a week was all that remained before he moved into an assisted living center.

I’m not really sure what I’ll do with my extra time when I don’t have to provide daily care. Something will emerge. Or someone.

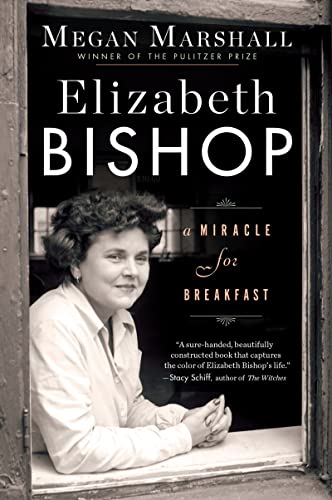

Dad wanted me to read some poems aloud. I’d recently picked up an anthology of contemporary American poetry and he chose Days of 1964 by James Merrill and Filling Station by Elizabeth Bishop, a poet Dad reveres and actually met in Brazil during our family’s missionary service in the late 1960s. He can recite about a dozen of her poems.

I struggled with Days of 1964 with its weird punctuation and line breaks. There was some good grist in there about a staid domestic servant with a secret romantic life but the poem seemed so arch and lacked any blood.

Then I read Filling Station, a poem I had never encountered before. Read one stanza for yourself, about what the poet sees in the living quarters of the family that runs the filling station:

Some comic books provide

the only note of color—

of certain color. They lie

upon a big dim doily

draping a taboret

(part of the set), beside

a big hirsute begonia.

I set the book down, gathered my thoughts, and told Dad that Bishop had perfectly captured in theme what I do when I look for and see subtleties of humanity in homeless encampments. When observed, they suggest to me these people are still hanging on, and perhaps still can make a way out of life on the streets or in the willows.

It’s that Jack o Lantern in the battered RV or the potted Christmas tree outside a tent or original art hung up on the pallet shanty or the one-eyed pit bull as co pilot in the truck that can’t drive anymore.

Sometimes when I look I see nothing but squalor, insanity and drug derangement. But I’ll keep looking there on my next visit nonetheless.

I fear for my character when I stop looking and I fear for many of the homeless when I no longer notice the subtleties.

Dad said he chose that poem for me to read because he knew it would appeal to me because of the way Bishop noticed tiny details of humanity in an otherwise dirty and backward filling station. He said he’d recognized the same in me in our many conversations about homeless encampments. Indeed, I would say this was the subject of a majority of our conversations.

To think that my 90-year old father could link an Elizabeth Bishop poem to my observations of the homeless, well, that was pretty damn astounding.