Changeover: A Tennis Tale (Part 4)

In the spirit of Wimbledon, which began this week, I present a short story I wrote a decade ago, but have recently updated. Enjoy. And get out there and play tennis this summer.

The reinvention had to start with a new dynamic tennis story for Chet. In the past, Chet inhabited the role of a tennis scrapper, hustler, plodder, an indefatigable human backboard who wore down high school opponents like the Europeans always wore down the Americans on clay. Most high school players had no patience, no staying power on the court. That’s why so many scores were 7-6, 6-love and why Chet won most of his matches 2-6, 7-6, 6-love. He knew if he could hang with an opponent into the third set, he would always win. He always outlasted them. He did not have the tennis talent (or desire) to do this at the collegiate level, there was never any pretense about that, but in high school, the strategy took Chet a long way, to a 17-4 record in league and a fourth seed in the district tournament.

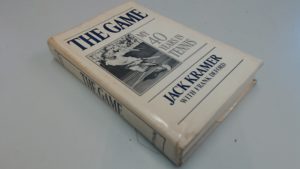

But that scrapper role was now history and Chet detached from it with perfect serenity. Chet knew he must assume a new role, the world beater in American culture, Mr. Love’s favorite obsession to teach about in class…Huck Finn, Sal Paradise, Thoreau, The Ramones, Jackie Robinson, Walt Whitman, Rachel Carson, Ida Wells, Upton Sinclair, early Elvis, early Brando, Orson Welles, Muhammad Ali, Lyndon Johnson and Jack Kramer. One of the books Chet read thoroughly for his project was Kramer’s autobiography, The Game: My Forty Years in Tennis. In fact, Chet could hardly put the book down. What interested him most was Kramer’s vivid retelling of his relentless lead role in the creation of professional tennis in the farcical era of amateurism. Jack Kramer had been a world beater in the finest American tradition, and his merry band of professionals barnstormed the world to places such as La Paz and Khartoum and played exhibitions in ice rinks and airport hangars with mosquitoes, nose bleeds and hangovers. In two decades, Kramer and company busted the ancient monopoly of tournament tennis and ushered the sport into the television age. There had been nothing like it in the history of professional sports and Chet knew that Jack Kramer, above all others, was responsible for the spectacular rise of tennis in America because he took it out of the elite clubs and into the city parks.

But that scrapper role was now history and Chet detached from it with perfect serenity. Chet knew he must assume a new role, the world beater in American culture, Mr. Love’s favorite obsession to teach about in class…Huck Finn, Sal Paradise, Thoreau, The Ramones, Jackie Robinson, Walt Whitman, Rachel Carson, Ida Wells, Upton Sinclair, early Elvis, early Brando, Orson Welles, Muhammad Ali, Lyndon Johnson and Jack Kramer. One of the books Chet read thoroughly for his project was Kramer’s autobiography, The Game: My Forty Years in Tennis. In fact, Chet could hardly put the book down. What interested him most was Kramer’s vivid retelling of his relentless lead role in the creation of professional tennis in the farcical era of amateurism. Jack Kramer had been a world beater in the finest American tradition, and his merry band of professionals barnstormed the world to places such as La Paz and Khartoum and played exhibitions in ice rinks and airport hangars with mosquitoes, nose bleeds and hangovers. In two decades, Kramer and company busted the ancient monopoly of tournament tennis and ushered the sport into the television age. There had been nothing like it in the history of professional sports and Chet knew that Jack Kramer, above all others, was responsible for the spectacular rise of tennis in America because he took it out of the elite clubs and into the city parks.

My new role, Chet envisioned, will also initiate a return to when tennis reigned, wood was king, American was thin, someone like Jimmy Carter could become President, when The Inner Game of Tennis was a monster bestseller and the basis for a PBS series, and when young boys would ride their bikes to the park, play tennis for hours while listening to Earth Wind and Fire and Stevie Wonder on the radio, and not need a hovering parent fretting over sunburn, dehydration, or obscene lyrics.

Chet reached into his bag, searching for something by feel. He found it. The Jack Kramer Autograph—the M-1 rifle of American tennis for almost two generations. He hoisted the racket aloft by its leather grip, then twirled it. He lowered the racket and moved his hand to its throat. He brought the racket to his noise and smelled: it smelled like wood, even after three decades of dank garaged exile! It was wood! This racket’s material had once been a stately hardwood tree grown from a seed! From the earth! What an exquisite piece of craftsmanship, of metaphor, a maple and ash laminate, lacquered, stamped with “Made in the USA” on the top of the frame. Chet swung a couple of lazy forehands with the Kramer. He had never hit with it before. The thought had never occurred to him.