Love, Peace and Slot-Machine Coffee (Lost Oregon Writing)

What follows is one of my favorite pieces of Oregon writing, from an anthology of creative writing from Oregon State Penitentiary inmates published in 1973 (see information below). I included it in my 2009 anthology Citadel of the Spirit and recently decided to take up a new project somewhat related to it: publishing the memoir of another contributor from that project, Smoky Epley. Before passing away in 2013, we became friends and I encouraged him to write up his life story of crime and incarceration. He did and completed it shortly before he died. At some point in the near future, I will publish his book, titled Auto, here on the blog and in e-book form. It’s truly quite remarkable and deserves an audience.

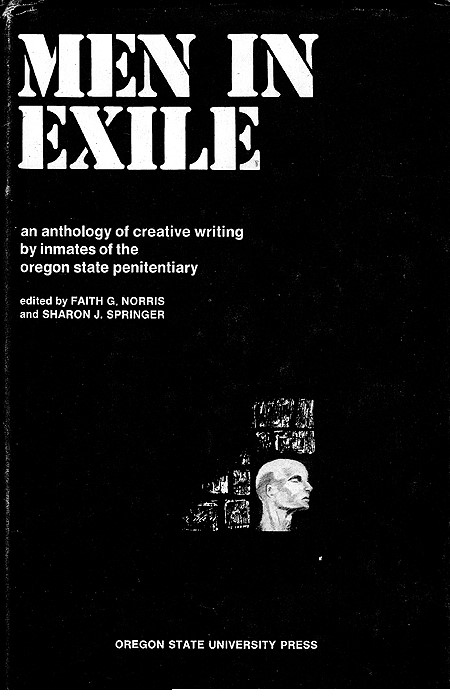

From “Love, Peace and Slot-machine Coffee,” an essay by Larry D.B. Smith, an inmate at Oregon State Penitentiary. The essay appeared in Men In Exile: An Anthology of Creative Writing by Inmates of the Oregon State Penitentiary, edited by Faith G. Norris and Sharon J. Springer and published by Oregon State University Press in 1973. The anthology was a result of Norris, a professor of English at Oregon State, teaching creative writing classes inside the prison and discovering significant interest and talent there.

Three years ago, when I was baptized and confirmed in the Catholic church, I was only vaguely aware of monasteries, monks, and the like. I had read stories that glamorized some of the monks of olden days, such a Friar Tuck of Robin Hood fame, but the reality of actually knowing a monk in a personal way was to come later. It came to me in prison, and when I was able to appreciate it most.

I had experienced a number of misfortunes, or so I thought. Things had not gone exactly the way I felt they should have gone. In spite of having worked very hard to earn the privilege of educational release, I had been denied this privilege. I met with similar denials when asking custody reduction, and again when asking for an early parole hearing. Reasons given by the authorities were not very well substantiated, and it seemed that the denials had been arbitrary. I was pretty bitter, and my studies were suffering from it. My visitors were too. The very person who had encouraged me to further my education now saw that there was a chance that it could boomerang and destroy everything that had been built up so carefully.

Unbeknownst to me, he spoke to one of the monks at a nearby abbey about me. Brother Francis sent word: did I care to correspond with him? He would like to have a “pen-pal.” Sure, why not? Letters from outside are always welcomed and Brother Francis offering to exchange letters was the beginning of a friendship. I didn’t realize just how great a friendship it would become until we exchanged several letters and I naively asked when he would be coming to see me on a visiting day. I was unaware that monks never leave the monastery for friendship visits, and rarely for any other reason, medical and church business excluded, of course.

The next letter I got was one that mirrored his frustration of having to break it to me that visits between us just weren’t in the cards, until I could visit him there. It is considered a distraction from the monks’ purpose to fully serving and thinking of God to go into the outside world. When they go into the Brotherhood, they renounce everything worldly for the cloistered life.

I’ll never forget Brother Francis’ words, “The chances for my coming to see you are quite slim. However, in the unlikely event that I should obtain permission from the Abbot, perhaps you should know what you will be meeting. I’m five feet one inch small, fifty-eight years young, with a map completely hidden behind a big beard and a perpetual smile on my face, and a funny-bone that causes me to laugh almost too much.” That proved to be an apt description.

The following Saturday, a friend of mine went to the Abbot and explained why he felt Brother Francis’ trip here would be justified. The Abbot felt the same, apparently, for he granted the necessary dispensation that permitted my friend to bring Brother Francis here. By the time we had to say goodbye, I felt that I had known this remarkable man all my life, and it was a reluctant parting when I learned that the trip could not be repeated.

Brother Francis and I began our conversation by comparing our respective circumstances. It was amazing to me that, here, I have so many liberties which I take for granted, while at the abbey, he was restricted beyond the average person’s comprehension. My few restrictions seemed to be pretty inconsequential by the time I learned that he had been in the monastery more than forty years—since he was seventeen—and had made only this one trip outside for a friendship visit in all that time. The only other trips outside had been to the optician’s, and to make the trip from Massachusetts to New Mexico, where a new colony was formed, then from New Mexico to Oregon.

Until about three years ago, the Brothers were not permitted to speak to each other except in the event that their work or safety depended upon necessary conversation. They could speak to the Abbot or any of their spiritual leaders when they sought advice or had a problem, but sign language was used otherwise. Then the silent system was relaxed. Even now, I learned, there is not an excess of talking, and the little talk there is is not useless chatter that we in the outer world are accustomed to. However, we chattered like two squirrels for over an hour.

Brother Francis asked if I might not like to share some coffee with him. The visiting room has a coffee machine, from which visitors and the inmates may purchase coffee (or a passable imitation) for a dime. I said yes, that would be nice. He asked me if I would show him how to operate the machine and then it began to dawn on me just how far out of touch with the outside world this man has been for forty years. We sat and sipped coffee and I remarked that this coffee must leave a lot to be desired, compared to monastery coffee. He said yes, “slot-machine” coffee could stand some improvement.

Later, in his next letter to me, he said, “I must agree with you that your slot-machine coffee isn’t the best, but I enjoyed that cup with you more than any I’ve had in quite some time.” Since that day, I’ve had a couple of cups with my friend who brought Brother Francis to the prison and another friend, and it even tasted better to me.

Brother Francis explained why the abbey coffee has better flavor: “It’s prepared by people, for people, not by a machine. People prepare things with love for people they love, while machines have no love for people; all they love is money.” That’s about as good a comparison as anyone could have given. If you don’t put a dime in the machine, it won’t give you a thing. The one we have occasionally has the option of taking the dime and thumbing its mechanized nose at the waiting customer. You can kick it, cuss it, or go sit down and cool off with a Coke, but it won’t give up the dime, and it won’t give up a cup of coffee.

In my discussion with Brother Francis, I talked about my college classes and the hobbies I like, and he told me of his woodcarvings. The proceeds from the sale of his carvings are shared with a T.V. program he likes, one of the few authorized programs they watch. I felt that he would have little trouble selling his carvings with such a noble cause profiting from it.

It was beautiful visit, and I was reluctant to end it so soon, but I knew within myself that somehow it had served a greater purpose than merely a social visit. It had brought me to a better understanding of myself. I realized that my disappointments were self-imposed, and in seeing and touching and talking with this wonderful example of selflessness, I found myself leaving the visiting room surrounded by an aura of calm that was new to me. It was not so strange, however, since it came Special Delivery, with brotherly love, from someone who cared enough to send His very best, Brother Francis.