Thinking About Jim Harrison, Dalva and My Future

During the recent upheaval in my life, I reread many books from 20-30 years ago that made a big difference in my life back then, wondering if they still had something to offer as I was going about trying to repurpose myself.

War and Peace—no. The Scarlet Letter—hell yes. Anything by Hemingway—no. Everything by Jim Harrison—yes, revolutionary yes.

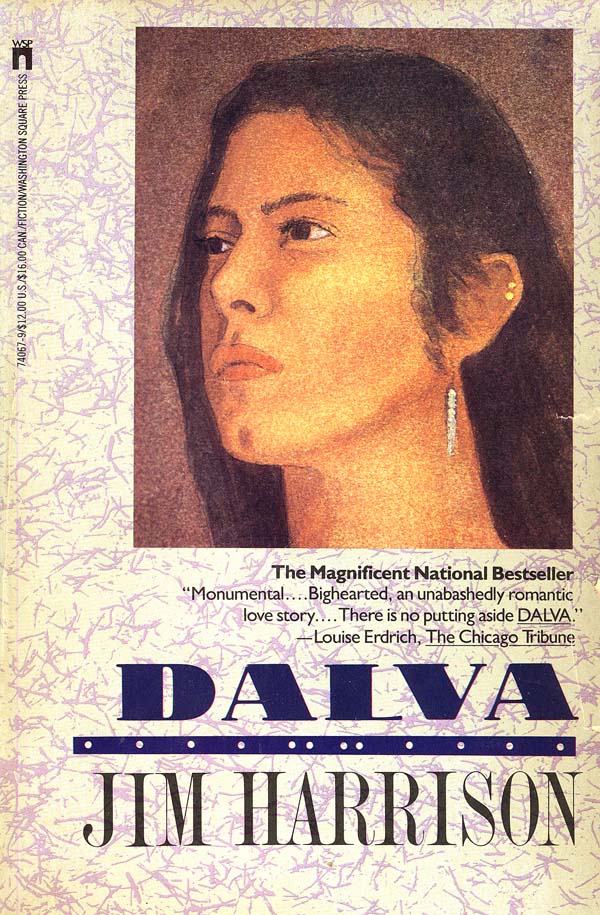

Jim Harrison died a little over year ago, and at the time I wrote a tribute to him that was published in a local magazine. What follows is an updating of that piece with further reflection because the writings of Jim Harrison, particularly his 1988 novel Dalva, my favorite American novel of all time, have showed me the way I want to proceed anew, just like they did 20 years ago. Somewhere along the way, I lost something critical and transforming that his writing had given me.

Almost every published writer I know can recall the moment when the desire to become a writer transcended mere fantasy and crystallized into hard reality—meaning, I’ve got to do this!

My moment occurred on March 10, 1997 in a NW Portland bookstore. That was the day I met Jim Harrison, celebrated author, poet and Western literary icon, who died March 26, 2016 from heart failure at the age of 78.

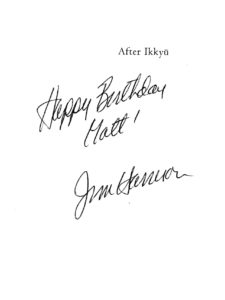

My encounter with Harrison landed on my 33rd birthday and lasted about a minute. It occurred at a signing for the release of his new collection of Zen-inspired poetry, After Ikkyu. My then girlfriend, soon-to-be wife, Cindy, had bought the book earlier that day for my birthday. She surprised me with it in the Pearl District loft I owned and where we lived, and then shocked me with the information that Harrison was appearing—right now!—at the bookstore ten blocks away. She told me to get going.

My encounter with Harrison landed on my 33rd birthday and lasted about a minute. It occurred at a signing for the release of his new collection of Zen-inspired poetry, After Ikkyu. My then girlfriend, soon-to-be wife, Cindy, had bought the book earlier that day for my birthday. She surprised me with it in the Pearl District loft I owned and where we lived, and then shocked me with the information that Harrison was appearing—right now!—at the bookstore ten blocks away. She told me to get going.

I ran to see Jim Harrison with his book in hand. I see now I was running to change my life. Sometimes we run and we don’t even know the reason we’re running. Jim Harrison’s writing made me run that afternoon. To that point in my life, I had read every published work by Harrison except his debut novel Wolf, starting with his collection of novellas, Legends of the Fall. His writing mesmerized me. When I read his work, it inspired me to live stronger, heartier, bolder, lustier, imbued by history, better informed by nature, with more meaningful original purpose, with more edge. His stories made me consider moving to the country because that’s where all of his fiction was set and these were much more interesting places than cities, particularly Portland. Harrison also made me want to own a dog, because he created characters who cooked for their dogs, and I loved that image. He wrote: “There is something about doing a favor for a dog that calms you down.” I later discovered that was about the truest line ever written in modern American fiction.

The line outside the bookstore was long, going well outside the door, spilling out into the sidewalk. I waited in silence and heard others talk about their passion for Harrison’s writing. I had never seen an author in person before and really didn’t know what to expect or how to act.

There he was sitting at a table. A large man. He had one eye missing from a childhood accident and was sipping red wine from the biggest goblet I have ever seen. It must have held the contents of an entire bottle. Behind Harrison, stood a gorgeous Native American woman, who handed him this or that item or book, depending on the fan’s needs.

I wish I could remember exactly all I said to him, but I don’t. It wasn’t memorable and probably a cliché. I did introduce myself and mention it was my birthday. Harrison said, “Happy birthday Matt” and then signed those words in my book.

He shook my hand and I drifted away from the table and out of the store. I walked back to the loft looking at Portland thinking something had to change. It had to be big.

In July of that year, I quit Portland and moved with Cindy to the upper left edge of Oregon, near the ocean, in the attempt to become a writer. I hadn’t written a word for publication and knew my time was running out. Seven or eight years later, it all started coming together, albeit unconventionally, and I realize now that Jim Harrison’s writing provided much of the instigation I needed. He got me into the country and he got me into dogs and he got me into finding the hearty stories of rural places that weren’t being told. He wrote: “What do stories do when they are not being told?”

Good question. I considered it daily as I go through life in the largely untold story of being a member of The Registry of Sexual Offense.

In his lifetime, Harrison published 21 novels, three collections of novellas, 14 books of poetry, two volumes of essays, a memoir, and a children’s book. My hands down favorite is the novel, Dalva.

A short time ago, I reread that novel, not the same copy from 25 years ago, because I had long since given that one away, and every other copy I found in thrift stores. The book came over me like a spontaneous revolution. I knew I had to find a way back to the land, the hard work on the land, like the ten years I served as caretaker of national wildlife refuge when I learned to live the life Harrison extolled. He kept extolling that life in his fiction and poetry until the day he died.

Harrison got away from me. I didn’t even know it was happening. I’m not sure how to return to him, his ideals, but I have a goal. That’s the frequent power of fiction; it can induce a better path for the reader’s future in a way that therapy can’t. Therapy can help in other ways. Then of course, there is the ocean for inducement, too. Harrison spoke to me about that as well.

Many lines of Harrison’s writing stand out to me, but the following passage is way up on the list. I don’t recall what book it came from.

I sat on numerous beaches and stared at the ocean until it was an ocean inside my head. The experience was a world away from the American idea of God as someone who drove around in a dump truck full of figurative candy to toss to deserving people if you beckoned him properly. The ocean was a god unknown, galactic…

This passage comes to mind almost every time I stand on the edge of the ocean. I’m going on 20 years at the Oregon Coast and have written 19 books since moving here. I’m the writing the book of my life right now. Rereading Harrison in moments of crisis has helped restore a sense of purpose for my creative and personal endeavors.

I never tried to write like Harrison. I just wanted to emulate his passion for everything. His writing helped unlock my passions, some of which I didn’t even know existed. One such passion was hanging out in dive Oregon Coast bars and observing local characters. I got that idea from Harrison’s fiction and recently published an e-book collection of my coastal dive bar stories, Oregon Tavern Age. It was he who wrote, “How can you experience the rich fabric of life in a locale without visiting the bars? The answer is, you can’t.”

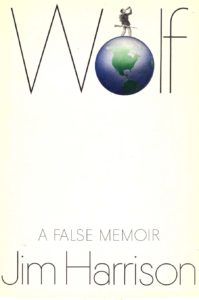

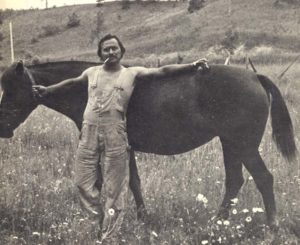

Not too long ago, I read for the first time Harrison’s debut novel, Wolf: A False Memoir, published in 1971. A great friend of mine who knew of my love for Harrison gave me a hardback first edition. Look at that truly remarkable cover and author photograph on back! Look at Harrison at 33! Preposterous and lovely!

Not too long ago, I read for the first time Harrison’s debut novel, Wolf: A False Memoir, published in 1971. A great friend of mine who knew of my love for Harrison gave me a hardback first edition. Look at that truly remarkable cover and author photograph on back! Look at Harrison at 33! Preposterous and lovely!

Wolf is a curious stream-of-consciousness novel that intercuts between the narrator’s hitchhike, lust and literary adventure around America and solitary camping experience in hope of seeing a wolf. It undoubtedly baffled critics and readers alike, but to me holds up incredibly well and presaged some of the ideas Harrison would later weave into his novels and novellas.

There is also one declarative sentence in Wolf worth repeating here. “There is no romance in being alone.”

One last thought about Harrison. A couple of years ago I was in the Warrenton Library and going through their boxes of giveaway books, VHS tapes and books on tape. I nearly fell over when I saw three cassette tapes titled Dalva by Jim Harrison, in a neat cursive script. I picked one up and realized someone had recorded themselves reading the entire novel, either for their own benefit or for someone else, a task that would take hours and hours of reading aloud, alone, into a tape recorder.

There was no name on the tapes, only a year, 1994.

There was no name on the tapes, only a year, 1994.

Who was this person? What was their intense connection to this book that compelled such a labor of love or necessity? I wanted to know this person. Most likely, he or she was dead and a relative had donated the tapes to the library. They weren’t even for sale.

I took the tapes home, but inexplicably never listened to them. I lost them some time during my ordeal when I wasn’t thinking straight and giving things away. But thinking about those tapes in recent days made me realize—I am not alone with my belief in Jim Harrison and the power of Dalva. I have no doubt it will work its magic on me again.