Still Teaching

Rain. Wind billows the American flag. Rain. Rain. Rain. The bedraggled men will slosh on up in the coming minutes—or they will not. They might miss the probation meeting and sleep off a rain drunk in a culvert or under the bakery.

Can a man sleep in a culvert that drains a coastal watershed when it’s raining like hell? Yes. I’ve met such a man. He told me he only stays dry if beavers build a few dams upstream. I am not making that up readers. This is what I have learned. What is this all about? I continue to assay.

A man on a phone walks up in the mist. A man in black rides away in the gray.

I wonder how much cannibalism for breakfast I’ll observe this morning. I almost passed out last time watching the meal.

Here comes a fat man in fleece. I don’t recognize him, but that’s impossible because I’ve seen him the last four months. His face and body have been completely rearranged due to injuries inflicted by indifference and marginalization.

He must have been a tasty repast for the cannibals.

A sweet pickup truck from the 1960s rolls up. Two-tone, blue and white. It has a potted Christmas tree in the back. It is an utterly incongruous sight.

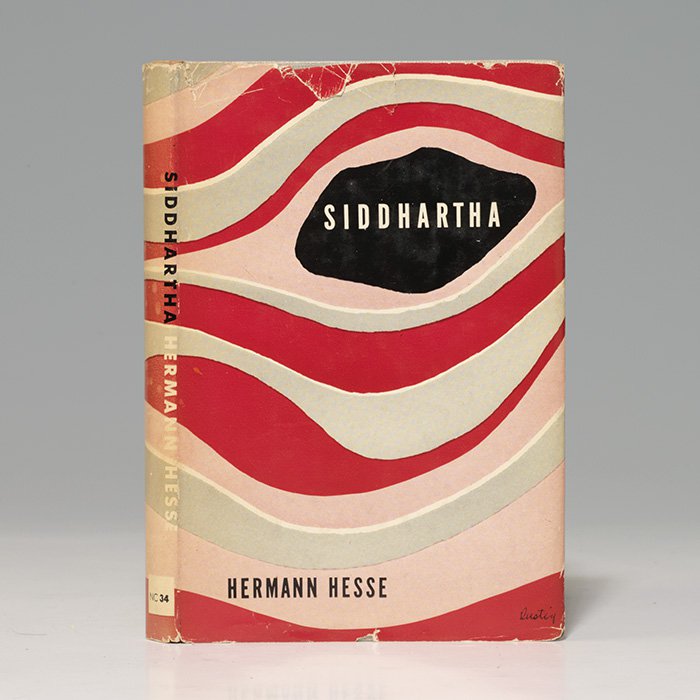

My mind drifts toward Siddhartha. “I can wait,” he tells his father, who has refused him permission to leave the comfort and privilege of a royal life. Siddhartha waits and waits and waits and receives permission.

I can wait. I am waiting with all my strength to return to a life of assisting others, assisting dogs and watersheds, calling attention to the cannibalism.

We assemble around a table. We hear grim news of those dead, busted, addled, back in prison, eaten whole, well, everything except the skeletons they sleepwalk around in.

There is a new young man. He remains silent until he asks, “How do you handle anger? I am so angry.”

His question goes around the table and each sane man gives his two cents. When my turn arrives, I say, “Have you ever read the novel Siddhartha?”

In my former life as a high school English teacher, I’d taught the novel with a unique method that changed students’ lives, as well as my own, for the better. In fact, I had developed a personal writing curriculum around the book that went far, far beyond the teaching of literature, and asked students to jump in the river of life. In that river, were the answers.

“No,” he says, but I detect interest.

I provide a 30-second summary of this classic novel and its eternal lesson of letting go of whatever you most desire, because that desire is causing you the most suffering.

“It’s short,” I say. “You can read it a couple of hours.”

He listens. He looks at me. I wonder when he’d last read a book.

I ask him if he can go to the library. No. I ask him if he has access to a computer and the internet to download it for free. No.

“I’ll get you a copy,” I say, “and I’ll drop if off here at the office for you to pick up.”

I have to drop it off at the office because he is living in the woods near a river.

He’s game. His anger is destroying his spirit, extinguishing his singular flame as a human being. The greatest novel ever written about the spirituality and ecology of rivers might be better than death, quack therapy, eternal pills, or prison.

And he could read it beside a river. He could jump right into the metaphor, splash, if he grasped the concept of metaphor, and I think he could because I taught it to him right then and there and never used the word metaphor.

We get up to leave and I pat him on the shoulder and whisper: you can make it.

I have a teaching mission and it feels energizing. It immediately brings to mind an incident from two years ago, where I stood pilloried before a judge, and she said I had forever “forfeited” my right to teach.

Later that afternoon, I hunt down a battered copy of Siddhartha and print out my list of journal prompts I’d devised for the instruction of the novel. I enclose the prompts within the book, along with a note explaining their purpose and that I would be happy to read anything he writes. I include my address.

I drive to office and leave the book with the receptionist.

We’ll see. I have no expectations. I have let go of all of that.