Dogs Raining (Reigning) in My Mind Part 13

This was written while I was surrounded by eight dogs on a sultry overcast day near a slack river.

In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville observed the Trail of Tears and recorded perhaps the saddest moment in history of American dogs and certainly the most agonizing account of humans having to leave their dogs behind:

At the end of the year 1831, whilst I was on the left bank of the Mississippi at a place named by Europeans, Memphis, there arrived a numerous band of Choctaws (or Chactas, as they are called by the French in Louisiana). These savages had left their country, and were endeavoring to gain the right bank of the Mississippi, where they hoped to find an asylum which had been promised them by the American government. It was then the middle of winter, and the cold was unusually severe; the snow had frozen hard upon the ground, and the river was drifting huge masses of ice. The Indians had their families with them; and they brought in their train the wounded and sick, with children newly born, and old men upon the verge of death. They possessed neither tents nor wagons, but only their arms and some provisions. I saw them embark to pass the mighty river, and never will that solemn spectacle fade from my remembrance. No cry, no sob was heard amongst the assembled crowd; all were silent. Their calamities were of ancient date, and they knew them to be irremediable. The Indians had all stepped into the bark which was to carry them across, but their dogs remained upon the bank. As soon as these animals perceived that their masters were finally leaving the shore, they set up a dismal howl, and, plunging all together into the icy waters of the Mississippi, they swam after the boat.

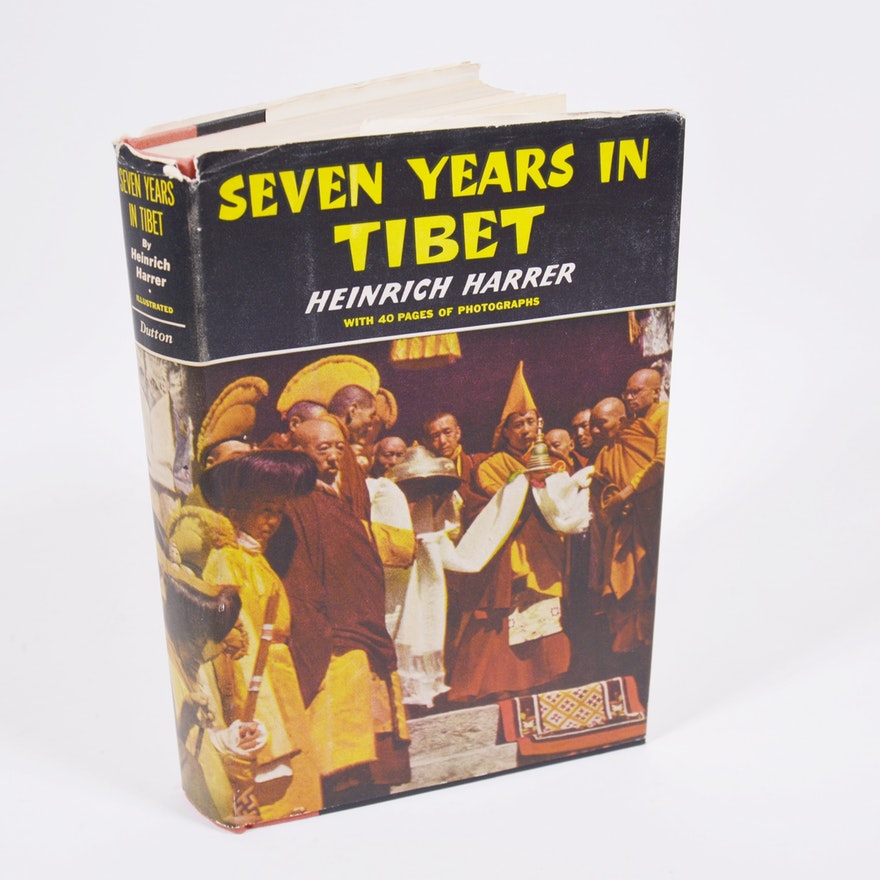

Heinrich Harrer’s classic 1954 memoir, Seven Years in Tibet, recounts another agonizing story of a human having to leave a dog behind. After almost two years of walking 2000 miles, through countless ice and snow covered passes of the Himalayas, and suffering unimaginable deprivation, Harrer, with a dog that had accompanied him for most of his journey, was poised to enter the secret kingdom of Tibet. The dog was oddly nameless in the book, but Harrer clearly loved it and was saddened when it simply couldn’t walk any further. He left the dog behind in a village and continued, where, in short order, he would meet the young Dali Lama, become his tutor and friend, and transform the world’s understanding of Tibet. The dog was left entirely out of the 1997 movie version starring Brad Pitt. Pitt reportedly nixed it from the script.

In the Mu Koan, widely considered one of the essential koans in Zen Buddhism, a monk asked the Master, “Does a dog have a Buddha nature or not?” The Master said, “Mu.” (No.) What is generally not recorded in print, however, is the Master’s response to the Monk after saying “no.”

“Don’t ask me, ask the dog.”

I have never met a phony dog in my life. I always wanted to date a woman with dogs who occasionally would rise before me in the morning and walk her dogs by herself. In the rich history of writing by dogs, Eugene O’Neill’s dog, Blemie, wrote perhaps the most moving example, The Last Will and Testament of an Extremely Distinguished Dog. It is a staple at dog wakes and funerals. A few memorable lines:

I realize the end of my life is near, do hereby bury my last will and testament in the mind of my Master.

I have little in the way of material things to leave. Dogs are wiser than men.

There is nothing of value I have to bequeath except my love and my faith.

It is painful for me to think that even in death I should cause them pain.

Dogs do not fear death as men do. We accept it as a part of life, not something alien and terrible which destroys life.

It would be a poor tribute to my memory never to have a dog again.

I want to write a book about the dogs accompanying their masters in the new American diaspora, a gigantic diaspora unparalleled in our nation’s history, a nation with many diasporas in its history, some documented in song (the Blues), some forced unconstitutionally (Japanese-Americans during WW II), some enshrined in myth (The Oregon Trail), some reversing previous expulsion (Mexicans reoccupying lands stolen through 19th century American imperialism) some with dogs and others dogless, some violent and some existential, some not even of human disposition, but animal, wolves and buffalo. And of course, there is the destructive diaspora of the Pacific Northwest salmon from their natural habitat, only to have humans invite them to return as fake hatchery fish to fake watersheds. This new American diaspora is largely unreported by the media, and if covered at all, lumped into a story of gentrification and homelessness, of addled minds, of the civic disturbance it creates, and almost exclusively framed as an urban story, where the presence of dogs is unnoticed, but the dogs (some cats, a few ferrets and snakes) are the crucial glue holding people on the move and in the margins together. I have seen this diaspora with my own eyes. I may very well part of it myself. I have seen Americans checking out in numbers unprecedented in our history. I have met many dogs of the diaspora. I really like them because they exude compassion like no other dogs I’ve ever seen.