A Conde McCullough Tribute

(I wrote this feature article for a coastal magazine last year, but it never ran. The topic is one of my favorites, Conde McCullough. At long last, there is a proper tribute to his genius.)

On the west end of the Lewis and Clark River Bridge, on the outskirts of Astoria, stands the greatest outdoor display of interpretative history I have ever seen in Oregon. It is a sterling monument of collaboration between a state agency, a genius bridge builder, an artist, the private sector, schoolchildren, poetry and an ideal that bridges can be beautiful and not mere conveyance—and that we should also acknowledge their excellent makers.

Last May, the Oregon Department of Transportation dedicated this interpretative display on the history of the Old Youngs Bay and Lewis and Clark River Bridges. In attendance were the partners that created the remarkable exhibit, including its project designer, Suenn Ho from Portland.

Last May, the Oregon Department of Transportation dedicated this interpretative display on the history of the Old Youngs Bay and Lewis and Clark River Bridges. In attendance were the partners that created the remarkable exhibit, including its project designer, Suenn Ho from Portland.

The erection of the display coincided with the repair of the bridges, built in 1921 and 1924, and designed by Oregon’s master bridge builder, Conde McCullough. The display features purposely rusted panels, hand-drawn architectural drawings, a gear shaft, old photographs, salvaged materials from the repairs, a timeline of McCullough’s career, and a brilliant cutout silhouette of the master himself wearing a fedora!

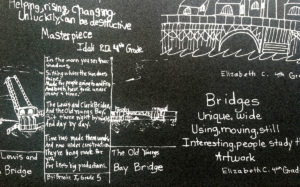

My favorite part of the exhibit is the handwritten inclusion of over 60 whimsical bridge poems and enchanting illustrations produced by Lewis and Clark Elementary students that artisans sandblasted into granite. One young bard named Vanessa wrote: Bridges, water, wow, wow wow / can’t stand their sight / It’s so beautiful / I love the sights, wow, wow wow.

Wow is the perfect word to describe McCullough’s bridges.

Wow is the perfect word to describe McCullough’s bridges.

Conde McCullough served as Oregon’s state bridge engineer for 18 years (1919-37) and is chiefly remembered for his elegant bridges along U.S. Highway 101 on the central coast that opened in the 1930s during the height of the Depression. McCullough’s bridges seized the public’s imagination with their distinctive and wonderfully eccentric art deco flourishes, such as stylish, often soaring arches of green steel, beveled columns, concrete obelisks, ornate railings and pedestrian plazas. They have since become nationally renowned landmarks of the Oregon Coast.

The Old Youngs Bay and Lewis Clark Bridges contain some characteristics that later comprised McCullough’s distinct style. The former includes beveled obelisks that mark the approaches from both ends, and atop each obelisk rests an odd little decorative lantern.

You get the feeling that McCullough was just warming up with Astoria and then later found his full measure as a designer with his other coastal bridges.

Ho’s project has masterfully recreated the kind of old school workmanship that distinguishes McCullough’s finest bridges. “I wanted something more than just a plaque,” she said. “This display was much more than just information about two bridges. I wanted to honor McCullough and the lost craftsmanship from that era, what was possible back then.”

Ho’s project has masterfully recreated the kind of old school workmanship that distinguishes McCullough’s finest bridges. “I wanted something more than just a plaque,” she said. “This display was much more than just information about two bridges. I wanted to honor McCullough and the lost craftsmanship from that era, what was possible back then.”

I remember feeling exactly the same about McCullough when I discovered his bridges and learned something about the man. Perhaps that’s why Ho’s display struck such a resounding chord in me.

In 2011, I published a quirky book called Love and the Green Lady, about my love affair with one of McCullough’s New Deal-era gems, the Yaquina Bay Bridge in Newport. I lived in Newport at the time and crossing that bridge every morning revolutionized my aesthetic and helped me understand that McCullough wanted more from a bridge than just civil engineering; he wanted art, beauty and to impart the human touch into his constructions.

The new interpretative display gets that exactly right in a method that astonished me. It’s easily the most imaginative explanation of McCullough’s work and ethos I’ve ever witnessed and I’ve seen them all. It truly deserves a visit and hands on inspection.

Toward the end of his career, McCullough wrote to a friend: “From the dawn of civilization up to the present, engineers have been busily engaged in ruining this fair earth, and taking all the romance out of it—there is no romance, nor poetry left in the world. If we only knew the truth, the decline of ancient Babylon and the complete dissolution of Sodom and Gomorrah were probably dated from the time they formed the first engineering society. However, I don’t know that there is anything we can do about it.”

Toward the end of his career, McCullough wrote to a friend: “From the dawn of civilization up to the present, engineers have been busily engaged in ruining this fair earth, and taking all the romance out of it—there is no romance, nor poetry left in the world. If we only knew the truth, the decline of ancient Babylon and the complete dissolution of Sodom and Gomorrah were probably dated from the time they formed the first engineering society. However, I don’t know that there is anything we can do about it.”

McCullough did do something about it. He built beautiful bridges along the Oregon Coast that we still use and admire today. His creative vision inspired others to follow him and one path led directly to the project near the Lewis and Clark Bridge, a display, I might add, that also had the good sense to declare in print: “Thank you Conde McCullough for your inspiration.”

When was the last time you read something like that on a historical exhibit?

(If you found this post enjoyable, thought provoking or enlightening, please consider supporting a writer at work by making a financial contribution to this blog or by purchasing an NSP book.)