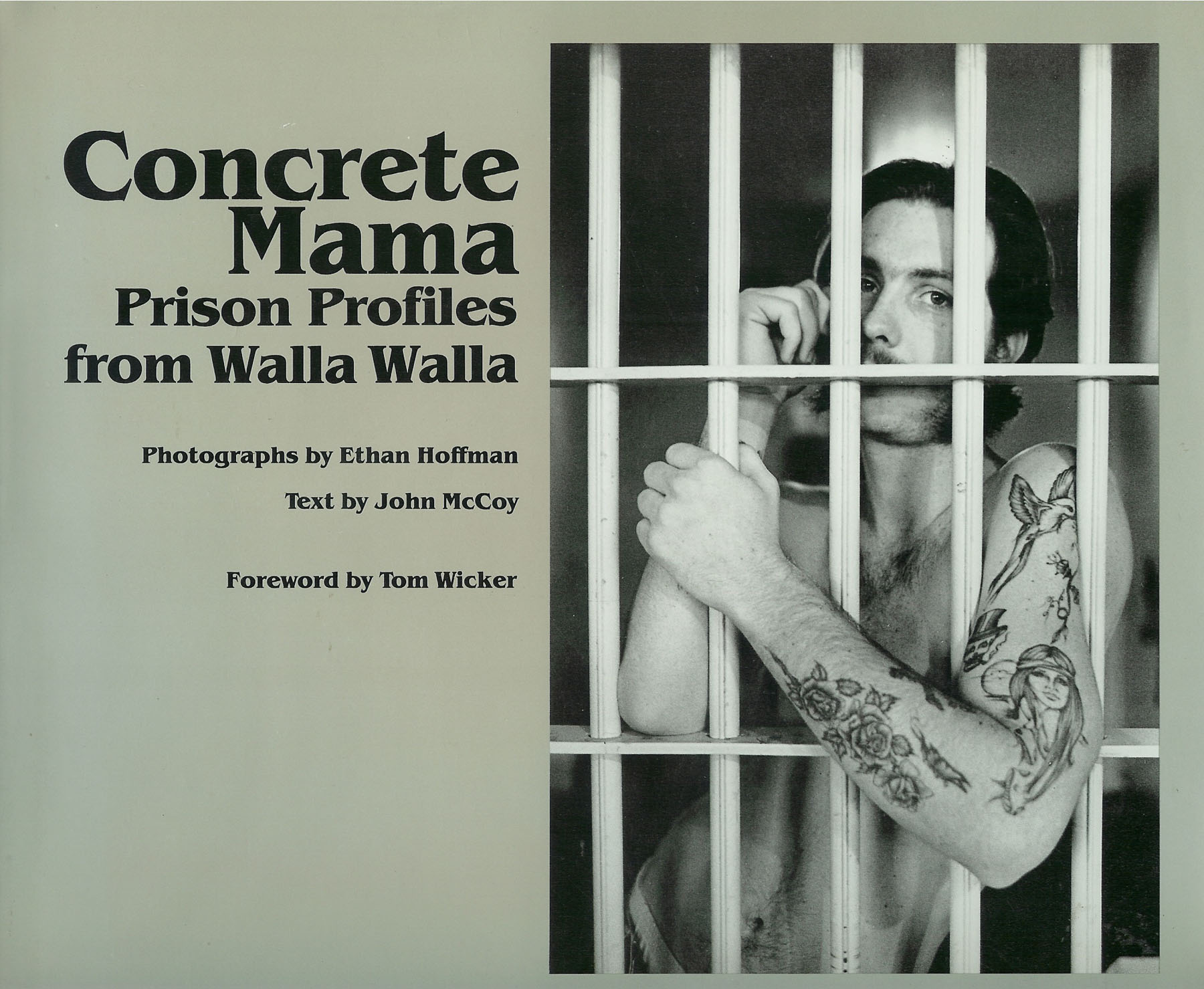

Concrete Mama

About a decade ago, I found myself in The Dalles, so naturally I went to Klindt’s Booksellers, the oldest and arguably the funkiest book shop in Oregon.

I told the proprietor I wrote the Lost Books column for the Oregonian and he said, “You’ve got to feature Concrete Mama.”

Concrete Mama. The title was unknown to me but I instantly envisioned a forgotten 1960s memoir by a woman who rode her Harley down Highway 101—and rode it topless.

“I’ve never heard of it,” I said.

“Just look it up. It’s a classic.”

So I did and the proprietor was right. Concrete Mama: Prison Profiles from Walla Wall is a classic, a Pacific Northwest classic of reportage, photography and history.

In 1978 two beginning journalists, a reporter named John McCoy and a photographer named Ethan Hoffman spent four months investigating life inside Concrete Mama, or, as it’s officially called, the Washington State Penitentiary, located in Walla Walla.

McCoy and Hoffman had covered the penitentiary for the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin as part of their regular beat and become fascinated by it. They hoped to deepen their coverage but were rebuffed by an editor.

So they quit their jobs, somehow won permission for daily access to every part of the prison, and went to work documenting the story through words and pictures. It wasn’t easy, and they had to earn the trust of the inmates, parry the guards, assuage the wardens, and suppress their own fears, but McCoy and Hoffman pulled it all off and turned in an incredible performance of journalism.

In 1981 the University of Missouri Press published Concrete Mama: Prison Profiles from Walla Wall. The 196-page coffee table-sized book featured McCoy’s 12 crisp, revealing profiles of prisoners and other people connected to the prison’s operation, and over 100 stunning black and white photographs shot by Hoffman. The book also included an introduction by the prominent columnist Tom Wicker, who wrote of McCoy and Hoffman, “They went inside the walls, they looked, they listened, they learned, they sought to understand…”

Concrete Mama sold well and a second edition was printed. A year later, a soft cover version was released and then the book went out of print and has pretty much disappeared from most libraries and used bookstores. It’s now a rare book and some signed copies fetch $500 online. (I paid $200 for mine and that was a decade ago.)

At the time, the Washington State Penitentiary was widely considered one of the worst prisons in the country, replete with murder, overcrowding, drug abuse, racial tension, rape, and McCoy and Hoffman walked into a hellhole of clashing reform mandates, one progressive, the other hard line.

Quite frankly, considering how close the journalists interacted (mostly unsupervised) with dangerous convicts, both seem lucky to have walked away unhurt.

I am not steeped in the history of America’s penal system, but I think I know enough to believe that McCoy and Hoffman’s book documented the end of an era, when rehabilitation, conjugal visits, prison jobs, prison literary reviews, work releases, inmate councils, screening Deep Throat, and four men to a cell apparently were the norm.

Inside Concrete Mama, as McCoy and Hoffman showed without editorial comment or first person intrusion, some men worked on and rode motorcycles, kept pets, dressed as women, negotiated shaky arrangements with prison officials, and roamed the yards in total leisure.

All of that changed, of course, when American’s prison population exploded in the 1980s and 1990s and with it a trend of keeping many prisoners in almost total solitary confinement. The hard cruel line won the war, but we now know the terrible cost this mass incarceration and probation (millions and counting) inflicted upon people, taxpayers, and the communities they were allegedly trying to protect. We certainly aren’t better off as a society. Some officials and criminal justice reform advocates grasp this reality and are working for change. I hope in the near future I can contribute in some small way to this important cause. I’ve seen a lot the past couple of years. Actually, I’ve lived it.